Wide World of Sports is running a series during the lead-up to the Beijing Winter Games on politics at the Olympics. This article looks back on the 33-country boycott of the 1976 Montreal Summer Olympic Games.

When Rod Dixon arrived in Montreal for the 1976 Summer Olympics the great New Zealand distance runner feared for his life.

Forty-five years later he’s alive to tell of his experience in the midst of a 33-country Olympic boycott, but he was faced with so much dread at the time that he avoided the opening ceremony and was daunted throughout the entire Games.

READ MORE: Nadal’s ‘superhuman’ effort after five-hour epic

Dixon knows as well as anyone the complex marriage between politics and the Olympics.

He made his Olympic debut at the Munich Games of 1972, stained by the deaths of 11 Israeli athletes at the hands of Palestinian militant group Black September.

The 1972 Olympic 1500m bronze medallist didn’t compete in the 1980 Moscow Games because New Zealand was one of 65 nations that boycotted, in a protest against the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan.

And politics continued to make noise in the background of Dixon’s career when he competed at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles, which 14 countries, led by the Soviet Union, boycotted amid security concerns.

But never was Dixon more involved in the grappling relationship between politics and the Olympics than in 1976, when 33 countries withdrew from the Montreal Games in a protest against New Zealand’s participation.

Those countries – most were African but some Middle Eastern and Asian – had campaigned for the International Olympic Committee to ban New Zealand from the 1976 Games because the All Blacks had toured apartheid-era South Africa earlier in the year, competing with the racially divided country despite an embargo.

The IOC had imposed a ban on South Africa participating in the Olympics from 1964 and the suspension lasted until 1988, but the governing body refused to block New Zealand from the 1976 Games.

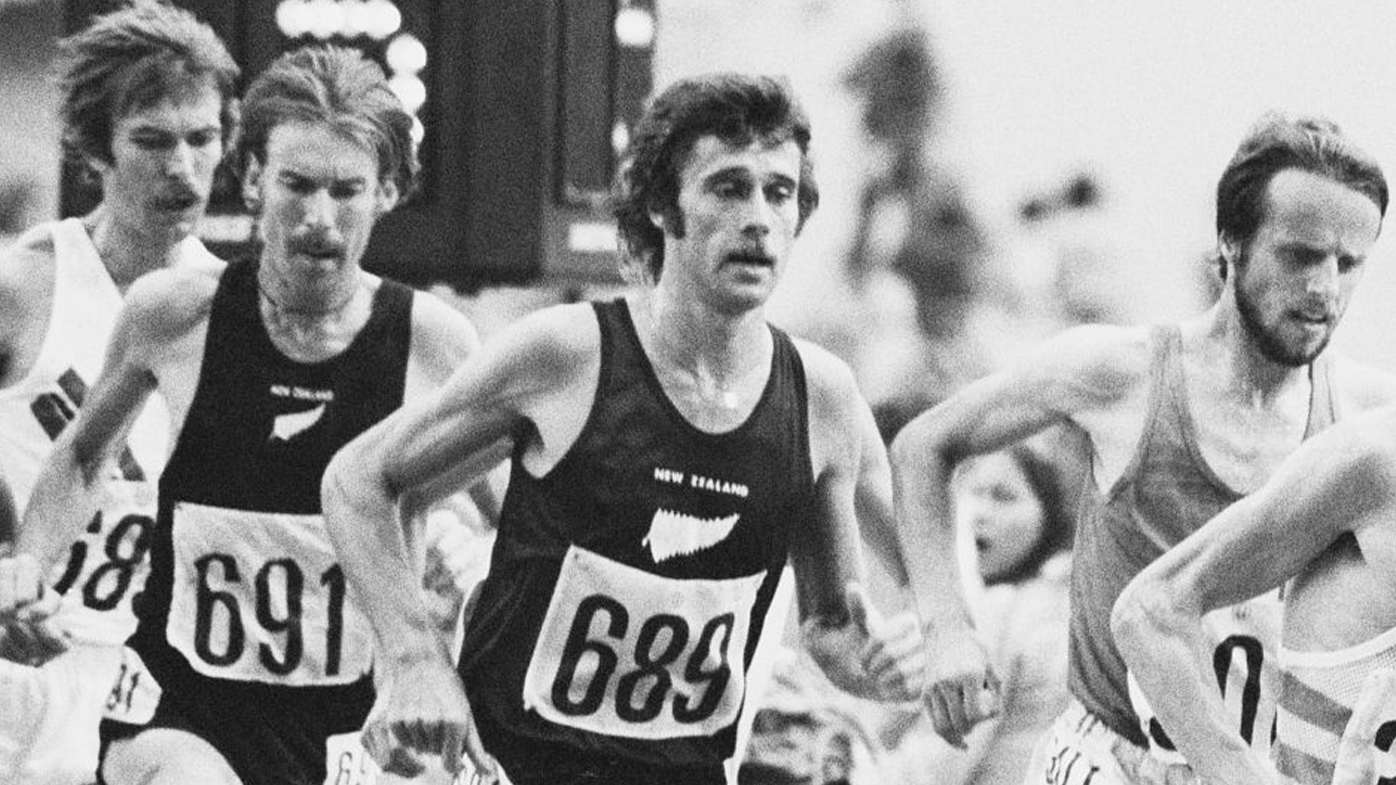

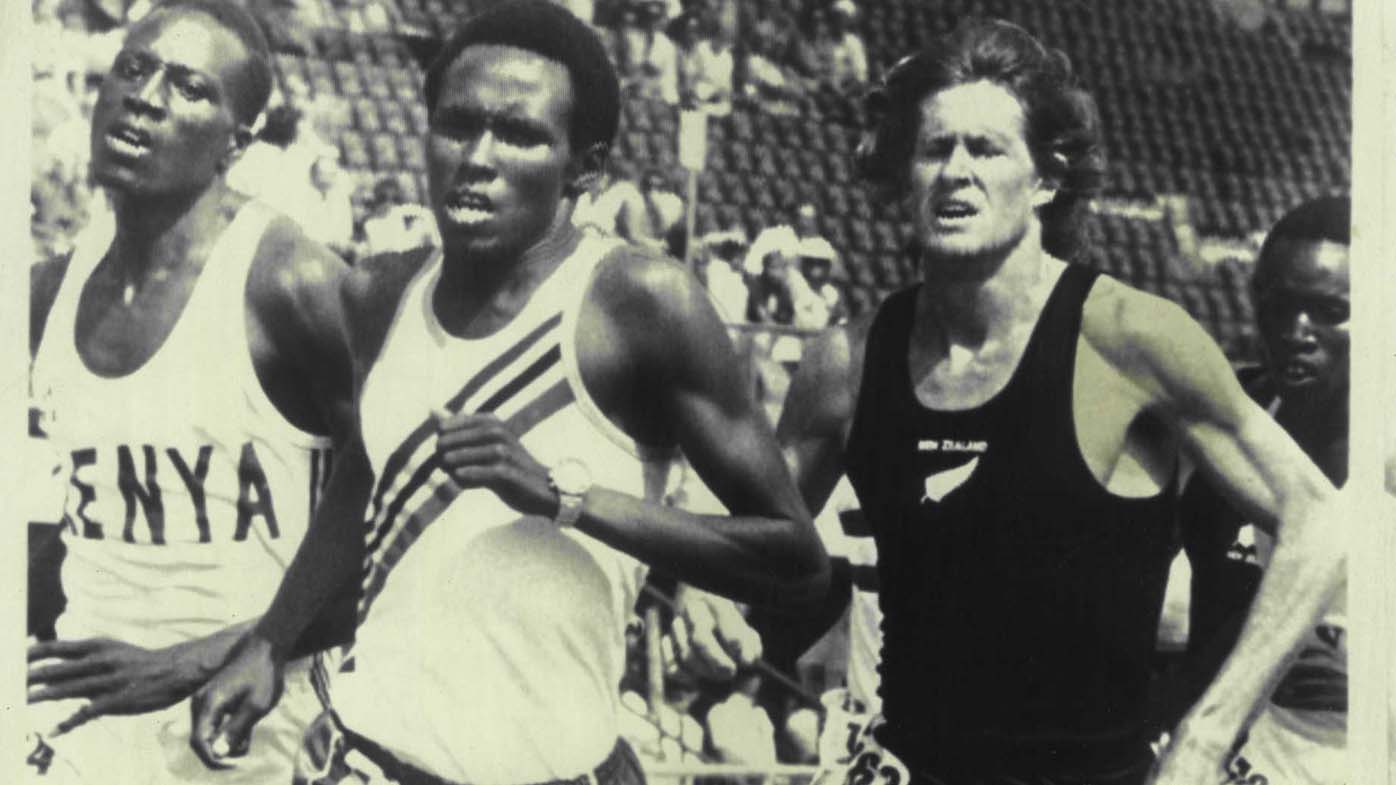

Dixon, John Walker and Dick Quax, all of whom skipped the Montreal opening ceremony out of fear, were more entangled in the political mess engulfing the 1976 Games than all other New Zealand Olympians. That was the result of being top distance runners, their extensive overseas travel for competition and the great success of black Africans on the track, in cross-country and on the road.

READ MORE: Nadal’s sharp response to claiming GOAT status

“We had a sprinkling of friendships and relationships with a lot of the African countries and … we were singled out,” Dixon tells Wide World of Sports.

“Their view was that if you value the friendships that you have you will go to the New Zealand Rugby Union and the government and prevent any further All Blacks teams going to South Africa to play rugby.”

Their ties with the Africans led the president of the Supreme Council for Sport in Africa, Abraham Ordia, to hold a meeting with Dixon, Walker and Quax in 1976.

But the three Kiwis were powerless in their attempts to combat the touring of the All Blacks, therefore putting them in danger.

“We were given a message that if you three attempt to walk into the opening ceremony (of the 1976 Montreal Olympics) that something will happen to you and it could be lethal and it could be life-threatening,” Dixon says.

“That was the message we got, so the three of us didn’t walk in the opening ceremony.

“And if they were going to suggest to us that the opening ceremony would be (a threat), there’s probably any other time they could have a potshot at us, too. I mean, we go to the training track. In the village, just because you have a dog tag on to say you’re an athlete it doesn’t mean you are.

“I was at Munich in ’72 when the massacre was taking place with the Black September coming into the village. You didn’t know how safe you were anywhere you went, whether you were being followed down town, if you were followed in for a beer.

“So, there was a concern and … a dark shadow … There was a bit of a cloud hanging over us throughout the entire Montreal Games.

“John was there with Arch Jelley as coach and John Davies was there (as Quax’s coach). I had to rely on those guys and their support. I don’t know if I was more emotional about it all than the others. I think we were all very well aware of the potential threat.”

READ MORE: Matildas coach feeling the heat after shock loss

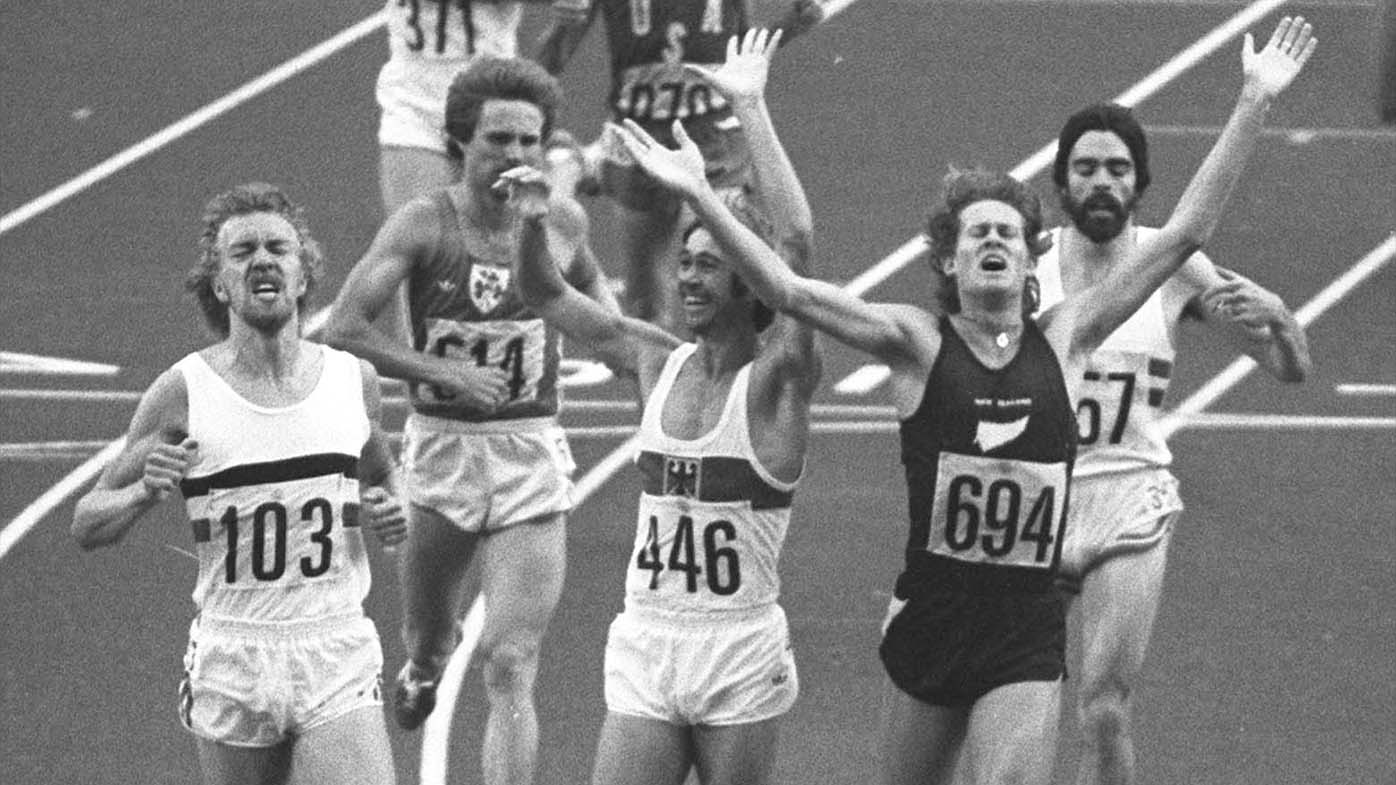

Despite the burden looming over the three brilliant New Zealand distance runners at the 1976 Olympics, Walker won gold in the 1500m, Quax collected silver in the 5000m and Dixon finished in fourth in the same event.

The absences of Tanzanians Filbert Bayi and Suleiman Nyambui, Ethiopian Miruts Yifter, Kenyan Joshua Kimeto and several others had stripped top quality from those fields, but Dixon nonetheless finds pride in the performances.

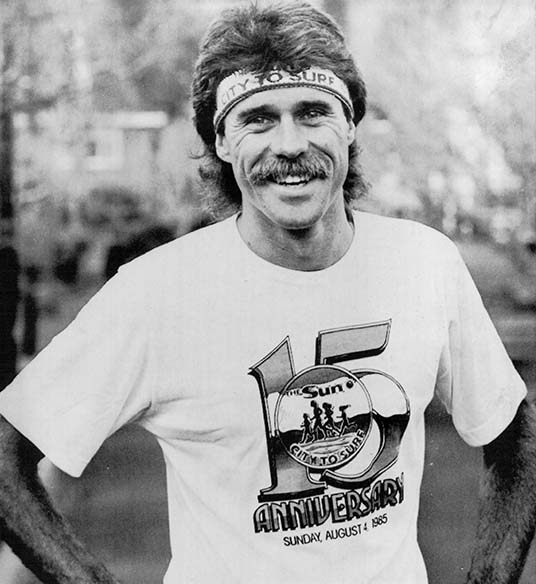

“The way we performed with that cloud hanging over us – the three of us shook our heads and said, ‘We got it done’,” the 71-year-old says.

“And we were able to withstand that potential lethal or life-threatening threat.”

When asked if he’s ever felt any guilt in competing in the 1976 Olympics given the context, Dixon gave a resolute “no”.

“We had openly competed with the (black) African athletes and, in fact, on a number of occasions … there were some white South African runners – Danie Malan was one – who came to Europe and wanted to compete against us, and we told race directors we would not compete against them because they were coming from a racially selected or a preventative country,” Dixon says.

“We were very, very aware that the black South African athletes were trying to come to Europe but were prevented.

“And so we therefore said, ‘If you’re not going to have an equal opportunity for all your people then we will not run against those selected’.”

Dixon became close mates with Bayi during their running careers and, despite Dixon’s decision to compete in the Montreal Olympics, he says they remain great friends today.

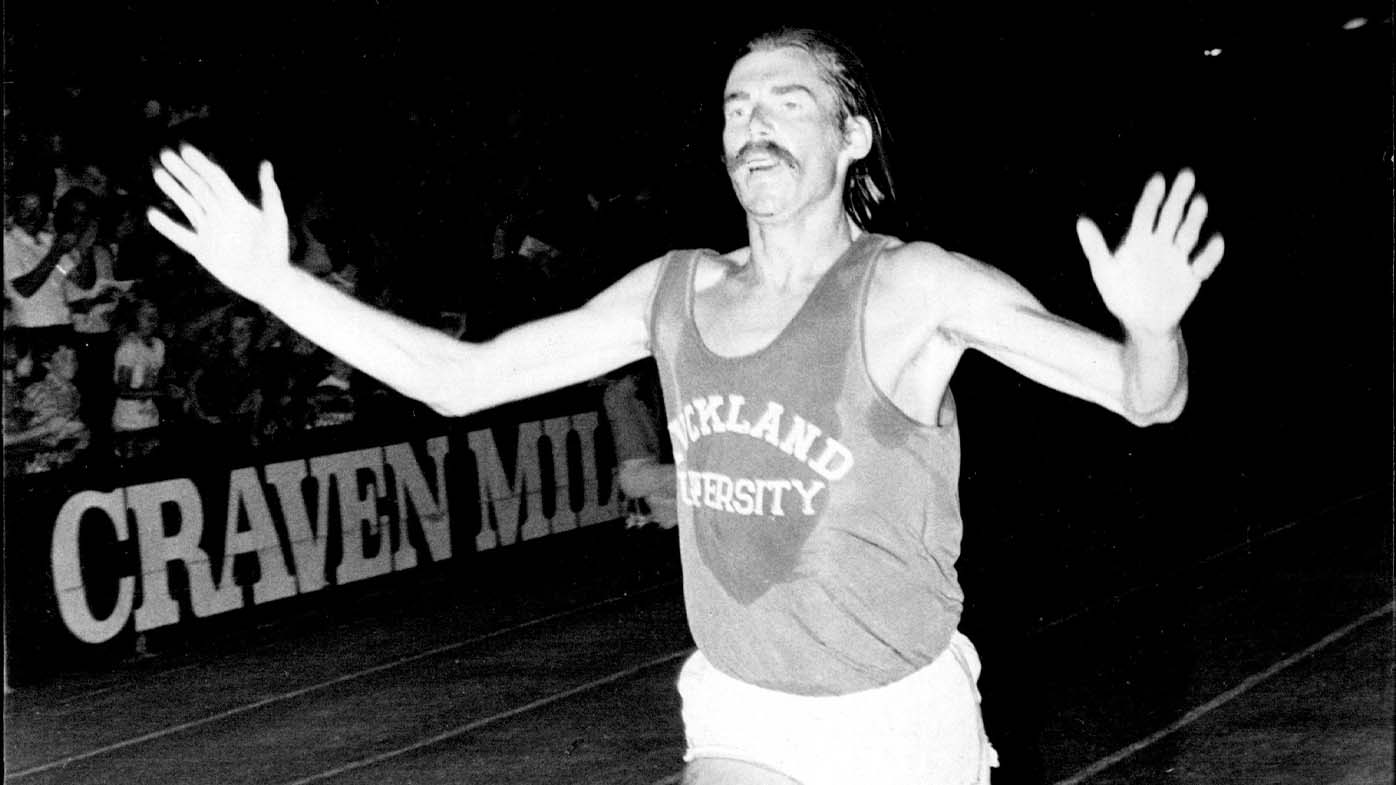

But the 1983 New York City Marathon champion reflects on 1976 with frustration, lamenting that his ties with African runners drew him into a game of politics.

Ordia, the president of the Supreme Council for Sport in Africa, was relentless in his attempt to use Dixon, Walker and Quax for political gain.

“He was bestowing upon us the right to go to the government and prevent any more All Blacks teams going to South Africa, but we said of course there was nothing we could do about this. We had no communication in a political sense,” Dixon says.

“And as much as we pleaded with them, ‘Please don’t bring us into it, don’t bring us into it, this is something that we can’t do, we just want to run, we want to run against the best in the world, we love our (black) African competitions and competitiveness’ … we were being used as a political pawn to do something which was completely out of our control.”

Dixon had a favourite saying in his time as a world-class runner.

“All I want to do is drink beer and train like an animal,” his training mates would often hear him say.

But life wasn’t always such a dream – for politics would get in the way.