Rafael Nadal’s painful left foot was numbed by multiple injections to two nerves throughout the French Open, the only way he has found to deal with a chronic condition he acknowledges puts his tennis future in doubt.

At any other tournament, Nadal said, he would not have persisted through what he called such “extreme conditions.”

READ MORE: Haney and Kambosos’ fathers almost brawl

READ MORE: Dubious call baffles greats in thrilling Pies win

AS IT HAPPENED: Haney’s unanimous decision win over Kambosos Jr

Ah, but five simple words uttered after he strung together the last 11 games of a 6-3, 6-3, 6-0 victory over an overwhelmed Casper Ruud in Sunday’s intriguing-for-a-handful-of-minutes final at Court Philippe Chatrier explained Nadal’s mindset: “Roland Garros is Roland Garros.”

And so even if Nadal, a French Open champion for the 14th time now at age 36, is in obvious ways different from Nadal, a French Open champion for the first time all the way back in 2005 at age 19, that desire to give his all, no matter what, to “find solutions” — one of his oft-used phrases — remains the same.

He is the oldest champion in the history of a tournament that began in 1925, and his hair is thinning on top. The chartreuse T-shirt he wore Sunday had sleeves, unlike his biceps-baring look of nearly two decades ago. The white capri pants that ran below his knees back in the day were long since traded in for more standard shorts; Sunday’s were turquoise.

Here’s what hasn’t changed along the way to his 22 Grand Slam titles in all, another record, in addition to his between-point mannerisms and meticulous attention paid to the must-be-just-so placement of water bottles and towels: That lefty uppercut of a topspin-slathered, high-bouncing forehand still finds the mark much more frequently than it misses, confounding foes. That ability to read serves and return them with a purpose still stings. That never-concede-a-thing attitude propelling Nadal from side to side, forward and backward, speeding to, and redirecting, balls off an opponent’s racket seemingly destined to be unreachable.

Nadal is nothing if not indefatigable, just as he was in consecutive four-hour-plus victories earlier in the tournament — including against Novak Djokovic, the defending champion and No. 1 seed — and again on this afternoon, even while competing on a foot devoid of any feeling.

“When you are playing defensive against Rafa on clay,” said Ruud, a 23-year-old Norwegian who was participating in his first major final, “he will eat you alive.”

Nadal said afterward he will try other methods of helping his foot — including, even, a way “to burn, a little bit, the nerve” — over the next week to see whether that might allow him to enter Wimbledon, where he has won two of his men’s-record 22 Grand Slam titles. Play begins at the All England Club on June 27.

If these new treatments do not work, Nadal said, then he will need to consider having what he termed major surgery — and, eventually, a “decision about what’s the next step in my future.”

“It’s obvious that with the circumstances that I am playing (in),” Nadal said, “I can’t and I don’t want to keep going.”

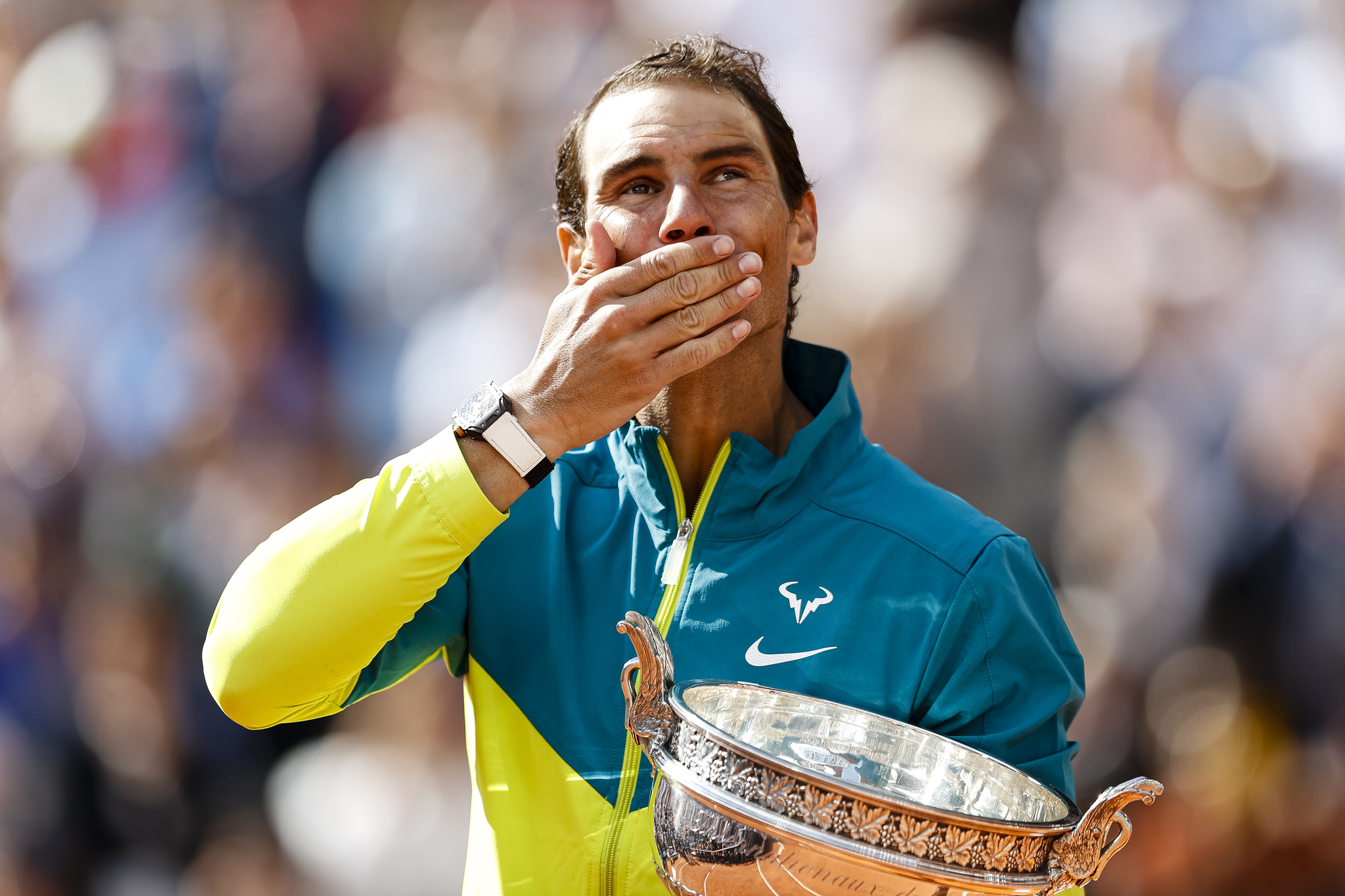

During the trophy ceremony, Nadal thanked his family and support team, including a doctor who accompanied him to Paris, for helping him, because otherwise he would have needed to “retire much before.”

“I don’t know what can happen in the future,” Nadal told the crowd, “but I’m going to keep fighting to try to keep going.”

Nadal added: “It’s obvious that I can’t keep competing with the foot asleep.”

Nadal told TV rights holder Eurosport in an interview on court after the French Open final that he played the match with “no feeling in” his left foot after getting an “injection on the nerve.”

He played so crisply and cleanly Sunday, accumulating more than twice as many winners as Ruud, 37 to 16. Nadal also committed fewer unforced errors, making just 16 to Ruud’s 26. After trailing 3-1 in the second set, Nadal would not cede another game.

“After that moment,” Nadal said, “everything went very smooth.”

Sure did.

The view from the other side of the net?

“I’m just another one of the victims,” Ruud said, “that he has destroyed on this court.”

One of the most indelible memories Ruud will take away from this day was hearing the announcer recite the long list of years Nadal had previously won the French Open: 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2020.

“Never stops, it seems like,” Ruud said. “That takes like half a minute.”

When the players met at the net for the pre-match coin toss, the first chants of “Ra-fa! Ra-fa!” rang out in the 15,000-seat stadium. Ruud would later hear folks in the stands do drawn-out pronouncements of his last name, so it sounded as if they might be booing.

Nadal is 14-0 in finals at Roland Garros, 112-3 overall. When this one ended with a down-the-line backhand from Nadal, he chucked his racket to the red clay he loves so much and covered his face with the taped-up fingers on both of his hands.

No man or woman ever has won the singles trophy at any major event more than his 14 in Paris. And no man has won more Grand Slam titles than Nadal.

He is two ahead of Roger Federer, who hasn’t played in almost a year after a series of knee operations, and Djokovic, who missed the Australian Open in January because he is not vaccinated against COVID-19.

For all that he has accomplished already, Nadal now has done something he never managed previously: He is halfway to a calendar-year Grand Slam thanks to titles at the Australian Open and French Open in the same season.

But if he can’t play at Wimbledon, which he has won twice, that doesn’t really matter much.

Ruud considers Nadal his idol. He recalls watching all of Nadal’s past finals in Paris on TV. He has trained at Nadal’s tennis academy in Mallorca.

They have played countless practice sets together there with nothing more at stake than bragging rights. Nadal usually won those, and Ruud joked the other day that’s because he was trying to be a polite guest.

The two had never met in a real match until Sunday, when a championship, money, ranking points, prestige and a piece of history were on the line. And Nadal demonstrated, as he has so often, why he’s known as the King of Clay — and among the game’s greatest ever.

“It’s something that I, for sure, never believed — to be here at 36, being competitive again, playing in the most favorite court of my career, one more time in the final,” Nadal said. “It means a lot to me. Means everything.”