* This is an edited extract from Campese: The Last of the Dream Sellers (Scribe, 2021) by James Curran, now available in bookstores

Trans-Tasman rugby rivalry virtually dictated that Wallaby legend David Campese’s career started and ended in sizzling encounters with All Black wingers. But in between that first meeting with Stu Wilson at Christchurch in 1982, and facing up to Jonah Lomu in Sydney in 1995, the changes to rugby worldwide were profound.

In the early 1980s, New Zealanders were quick to praise the startling talents of this raw, young Australian flyer. Campese was part of a dazzling Australian side which included the Ella brothers, Peter Grigg, Michael Hawker and Roger Gould. That team ran the ball from everywhere, nearly snatching a rare Bledisloe series win on New Zealand soil. In the wake of a tumultuous Springbok tour to New Zealand in 1981, the young Wallabies raised the spirits of a beleaguered Kiwi rugby public.

By the mid 1990s, however, New Zealand journalists demanded David hand over his crown to Lomu, rugby’s new Goliath. Where Campese had once used his famous ‘goosestep’ and scintillating pace to leave Stu Wilson stranded, by the time of the Bledisloe Cup match in Sydney in July 1995, Campese, like so many other wingers on the world stage at that time, was shaken by the Lomu freight train stampeding over and through the Wallaby defence.

Watch the 2022 Super Rugby Pacific season on Stan Sport. Start your seven day free trial here!

As the game headed into the professional era, Lomu was perfectly moulded to fit the need for a new type of sporting hero in a globalised age. Campese had been one of the game’s last amateurs but also one of its first professionals. Yet by this time his wizardry was giving way to overweening power; his ballet, to blitzkrieg.

Campese had arrived in New Zealand in 1982 as an unknown quantity, and, much to the displeasure of locals, professing ignorance of his more fancied opponent. ‘Stu who?’, he is reported to have said as he answered reporters’ questions about how he felt about facing up to the All Black tyro.

Campese had come from a working class background in Queanbeyan, or ‘Struggletown’ as it was known, situated near the capital, Canberra. He had played rugby league, mostly, as a youngster. And so arrived on stage not knowing the actors in the play he was about to break open.

READ MORE: Wallabies caught up in rugby’s COVID-19 chaos

READ MORE: Legend’s big legacy call for 2027 Rugby World Cup

READ MORE: ‘Tarnished’ Aussie ref gets apology from Springboks

In the pen portraits featured in the official programme from that first test, Campese’s occupation was listed as ‘saw miller’. There is something almost perfectly, if not deliciously, fitting about that job title, for what Campese did in his day job he was to effectively do to his All Black opponents that afternoon, and later, to teams the world over: slice through gaps and split defences.

A rugby correspondent would later write that whilst few would remember the scores in that series – Australia lost two tests to one – ‘Campese’s sparkling running, by contrast, will remain in the memory, a warm glow emanating on cold, dark nights’.

During that debut in New Zealand, Campese first exhibited in a Wallaby jumper what was to become known as his signature move: the ‘goosestep’. Journalists found the ability to describe it as elusive as the move itself. How to translate it from park to prose?

The ‘goosestep’ was a footloose shuffle that appeared to bamboozle defenders: a half-moment when it appeared Campese stopped running in mid-air, as if suspended on an invisible highwire, before taking off again at an even quicker pace.

To the spectator, it was the essence of a new flamboyance Campese was bringing to the game: as if he was inviting both opponent and spectator to hold their breath – to wait, even if for a split second – before the next instalment.

In the wake of Campese’s debut in Christchurch, the Sydney Morning Herald’s Evan Whitton observed that the ‘heavy thinkers of New Zealand rugby nearly went off their brains trying to describe the little number that David Campese unveiled for the stupefaction of his opponents. Was it … a Hesitation Waltz? A minuet? What?’

Whitton, though, got closer than most to its essence: ‘What he did was throw a foot out, and then bring it back before it touched the ground. The idea was to anchor his opponent before Campo blasted off round him. So it was a feint like nothing seen before, and it blew poor Stu Wilson, 27, veteran of sixty-nine first class matches for the All Blacks, and billed as the best right wing in the world, right out of the water’.

As the former All Black Grant Batty observed of Campese after the match, ‘that goose step of his is a marvellous touch of showmanship [and] just the sort of thing the game needs … it’s that little touch of uniqueness that makes him something special’. It was to enthrall crowds the world over in a career that saw him hold, for a time, the world record for test tries and the most number of test appearances by an Australian player.

Campese’s success on his first tour to New Zealand is now well documented. The Australian broadcaster Gerry Collins remembers overhearing a conversation in the crowd at Whangarei, where the Wallabies took on North Auckland in the tour’s penultimate match. The locals were comparing Wilson to Campese. ‘Wilson is so fast, sure’, the punter said, ‘but Campese, well, how do you catch the wind?’

By the end of the tour, on the eve of an improbable decider at Eden Park, the esteemed New Zealand rugby scribe TP McLean was praising these ‘wonderful … inspiring’ Wallabies for their success following the withdrawal of so many players before the tour – Campese being singled out ‘for that leg action [which] could win the Commonwealth 110m hurdles in footie boots’.

Back in Queanbeyan, the local newspaper felt that Stu Wilson ‘must see Campese coming at him in his sleep’. Wilson, to his credit, has never hesitated to praise Campese.

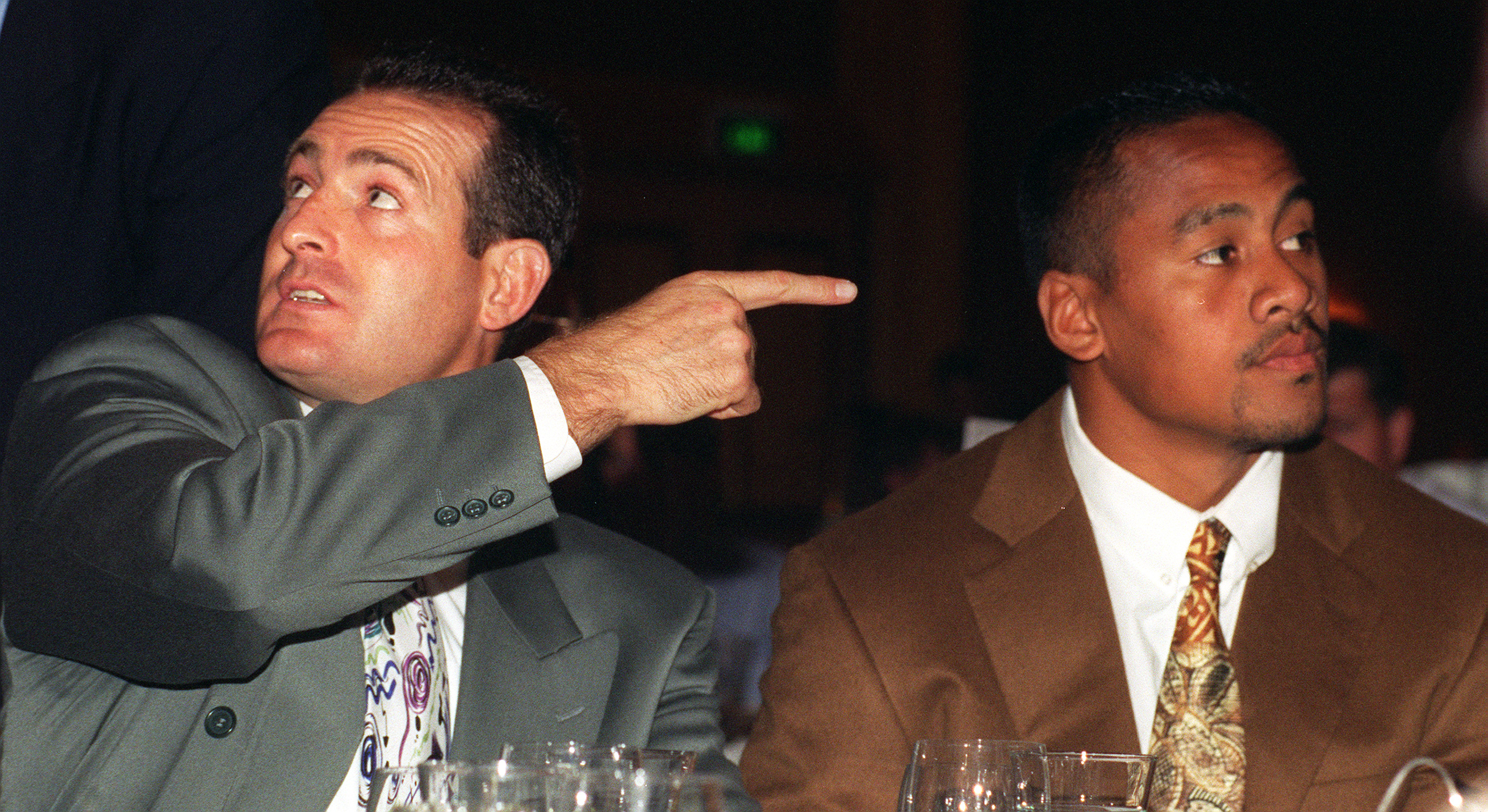

In between his encounters with Wilson and Lomu, of course, was Campese’s rivalry with John Kirwan. The writer was at Concord Oval in 1988 to watch Kirwan swat Campese away like a troublesome gnat on his way to two tries in that first test. The ledger, however, was squared when Campese turned Kirwan inside out at Dublin’s Landsdowne Rd during the 1991 World Cup in probably one of his most daring, mercurial tries: running across field on a diabolical angle towards the try line.

The try Campese then created for centre Tim Horan later in that half – with a blind ‘Hail Mary’ pass over his right shoulder, led a French journalist that day to conclude that the crowd had witnessed a masterclass, an elder handing down his life’s work, ‘as if leaving instructions on how he wanted the game to be played’.

But the game was changing, and fast. And Campese was trying to change with it. Players were simply becoming bigger, defences more organised, breakouts harder to initiate.

Prior to the 1995 World Cup, Campese’s increase in physical size was a talking point in the press. The will-o-the-wisp was well and truly leaving behind the lithe form that had slipped onto Christchurch’s Lancaster Park in August 1982. He had weighed in at 79kg on that occasion, and over the years his weight remained steady; even at the 1991 World Cup, he was still only 82kg.

But by 1995 he had bulked up to 91kg. He looked ‘more like a solid oak door’, said one profile, his bulk now putting him in the ‘John Kirwan league of wingers who can smash straight through their man if the need arises’. Campese now regrets it – he lost much of whatever pace he had left, and some of his famed agility.

The irony, of course, is that Wallaby success in that era, and Campese’s part in it, helped ensure Rugby’s ultimate passage to professionalism. Save for another world cup win in 1999, however, Australian rugby has been unable to recapture the dash and daring of the Campese era. The All Blacks, not the Wallabies, are now the global standard bearers for running rugby.

* James Curran is Professor of Modern History at Sydney University and a foreign affairs columnist for the Australian Financial Review.

– This extract originally appeared on stuff.co.nz and is reproduced with permission